Posted

on

in

Travel

• 1403 words

• 7 minute read

Tags:

Waterloo, Belgium

Today I visited the Waterloo battlefield. I’d visited the town of Waterloo and the Wellington Museum last year when I came to FOSDEM, but I didn’t have time to go to the actual battlefield site. I bought a ticket that was valid for a year for both the museum and battlefield site, so I was able to use the same ticket.

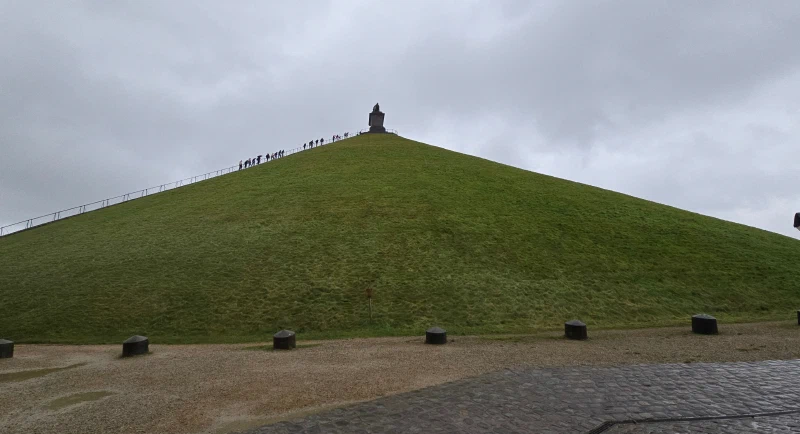

I started my day by heading from my hotel to Bruxelles Midi station where I managed to find the correct bus towards Waterloo. This went much better than my trip last year where I failed to flag down the bus. The bus took me right to the battlefield site. At the site, a huge mound was created a few years after the battle called the Lion’s Mound. In the early 1900’s, a panorama depicting the battle was created within a circular building near the mound. A more modern museum has been created underground connecting to the basement of the panorama. It was this museum where I started.

Quite frankly, the museum was not very good. Most museums on battlefields are designed such as to convey a narrative about the events leading up to the battle and the battle itself. Waterloo, of all battles should be such. However, any coherent historical context was greatly lacking in the museum. There was decent narrative around the events of the battle, but it was greatly lacking in detail about the masterful battlefield victory achieved by the coalition forces.

The events leading up to the Battle of Waterloo were a direct result of the French Revolution. The monarchies of Europe did not want the French revolution to spread through the continent, and launched two wars against the burgeoning French Republic. One particular individual rose through the military and political ranks during those wars: none other than Napoleon Bonaparte. Over the next decade and a half, Napoleonic France would upend the European balance of power with stunning victories across the continent.

He started by humiliating the Austrians in a masterpiece at Austerlitz during the War of the Third Coalition of 1805. Then, during the War of the Fourth Coalition the next year, his forces decimated the Prussian army in under a month with an 18th century blitzkrieg including the decisive twin victories at Jena and Auerstädt. He followed those victories by defeating the Russians and turning Poland into a French client state. However, cracks began to show in the French Grande Armée during that war. Russia managed to fight to a bloody draw at Eylau before being decisively defeated. Austria, which had sat out the previous war, declared war along with allies in the War of the Fifth Coalition in 1809. The Austrians managed to achieve a battlefield victory against Napoleon at Aspern-Essling before being defeated decisively at Wagram.

Napoleon looked undefeatable and he used his power to institute political reforms across his continental holdings, many of which were liberal by the day’s standard.

However not all was good in the Empire. A persistent insurgency in Spain which Napoleon had invaded in 1808 remained a quagmire until the French were ultimately expelled from the peninsula. But possibly the most important event of the Napoleonic wars was the ill-fated 1812 invasion of Russia where, despite sacking Moscow, Napoleon’s supply lines faltered and his troops withdrew through the brutal Russian winter. The Grande Armée suffered half a million casualties during the disastrous invasion greatly weakening its effectiveness.

The European powers saw a weakened French Empire and took the opportunity to form a Sixth Coalition. The weakened Emperor inflicted multiple defeats of the allied powers, but the alliances held and many French vassal states defected to the coalition. In a three-day battle and the largest European battle until WWI, Napoleon’s Grande Armée was encircled and routed at Leipzig. After the battle, Napoleon’s defeat was inevitable. Coalition forces invaded France, forced the Emperor to abdicate and sent him to the island of Elba, and reinstated the French Monarchy.

However, Napoleon did not stay in exile long. He returned the continent in early 1815 and all of the French forces sent by King Louis XVIII to stop him turned to his side. This Napoleon with renewed continental aspirations was an anathema to the continental powers who had spent the better part of the last two decades combatting the rise of republican and imperial France. The entirety of Europe allied themselves once more in a Seventh Coalition, declared Napoleon an outlaw, and declared war on the Emperor himself.

Napoleon quickly mobilized a new army and invaded Belgium hoping to engage and defeat the British allied army and Prussian army in detail. After sharp engagements of the British and Prussian advance forces on 16 June, Napoleon massed his troops on the 18th for battle against Lord Wellington’s allied army at Waterloo. As I described in my post from last year, the allied forces under Wellington valiantly held the critical Hougoumont château while being pressed hard in the centre during the afternoon. However, the coalition forces were highly coordinated and the Prussian army under Blücher arrived on the field in the late afternoon and evening threatening Napoleon’s right flank and achieving numerical superiority for the coalition. Pressed on three sides, the French line collapsed and a rout ensued. Napoleon himself was forced to flee to Paris and days later he abdicated for a second time and was sent in exile in the very remote island of St. Helena.

The victory at Waterloo was a true coalition victory. If Blücher had not been able to Wellington’s aid, the outcome of the battle would have likely been different. Napoleon might have been able to win the day and turn his forces against the Prussians successfully doing what he had done so many times before: defeating the enemy in detail. Despite this, it seems unlikely that Napoleon would have been able to effectively prosecute a protracted conflict against the allied great powers of Europe. However, conflict would have no doubt extended many more months or even years.

The museum failed to illustrate the tight coordination of the coalition forces, nor did it fully explain the critical junctions of the battle. However, they do have many artefacts of the battle and of the time period on display which was cool. I finished the modern portion of the museum and went up to the panorama. It is a very impressive painting portraying Marshal Ney’s cavalry charge.

After that, I went outside to climb the Lion’s Mound.

I climbed to the top and looked over the battlefield. Pretty much the entire battlefield is visible from the vantage point of the mound. The mound is located on top of Wellington’s centre. The strategically important Hougoumont can be seen to the right. To the left the Haye Sainte house where the French were finally able to bring their artillery to bear against the British centre can be seen. In the distance, the village of Plancenoit, which saw the heaviest fighting between Prussian and French forces, can be seen. Unlike many of the era’s battles, the entire battlefield is visible from a single terrestrial (albeit artificial) vantage point. It was amazing to see a spot where one of the greatest political and military minds of history was finally defeated.

Napoleon transformed Europe through war. The states he defeated adopted many of his military and political innovations. The corps system which allowed sections of his army to move quickly and independently allowed unmatched manoeuvrability and allowed Napoleon to repeatedly defeat his enemies in detail. The corps system is used in nearly every modern military. Napoleon’s use of artillery batteries in coordinated attacks repeatedly broke even the staunchest of lines. However possibly more important this his tactical innovations was his emphasis on merit-based promotions. At its height, the Grande Armée had top-notch commanders with seasoned troops who had fought alongside their commanders in many battles. Politically, many of Napoleon’s liberal reforms were adopted by states across Europe and laid the groundwork for the rise of democracies across the continent.

It was quite cold and drizzling while I was on the mound so I did not stay long. I descended and decided to eat a late lunch at the restaurant at the base of the mound. I had some nice spaghetti Bolognese.

I then caught the bus back to Bruxelles and called it a day.