Posted

on

in

Hackathons

• 3495 words

• 17 minute read

Tags:

Facebook Hackathon, Win, Hackathon, Prize, Hackathon Demo

Objectively, I’m pretty good at winning prizes at hackathons. I’m not entirely sure how/why, but I am. In this article I intend to try and describe some of the things which have helped me and my teams at hackathons. Please note that these are merely my experiences. Your mileage may vary.

This article was partially inspired by Yaron Malin’s post: Hackathon Winning Secrets. Yaron was on the team which won third place at the Facebook Global Hackathon Finals.

Before I can talk about how to win a hackathon, we need to be clear about the definition of a hackathon. A hackathon is not a competition where you try and crack into computer systems1. Rather, it is a competition where you are given a period of time (normally between 24 and 36 hours) to create a project. We call the projects hacks because they are very hacky, that is, they are not pretty when you look “under the hood”, so to speak.

Why You Should Listen to Me

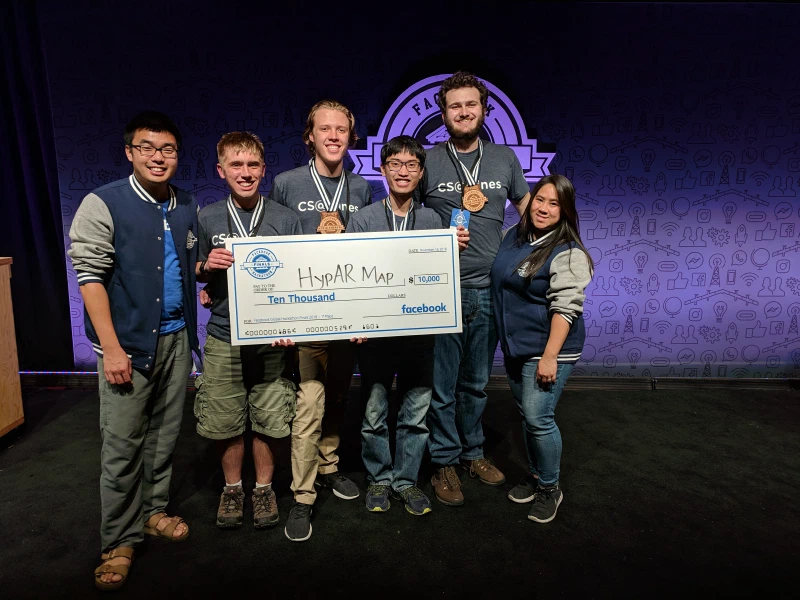

I have been to five hackathons and successfully created and demoed a project at each of them. At the Xilinx hackathon, my team won the Grand Prize. At MinneHack 2018, we did not win anything, but gained valuable experience. At HackCU IV, we won Judges Favorite, Best Use of AWS, and the Dish Network sponsor challenge. At MHacks, we won Best Use of GCP and the Facebook Best Social Good Hack award. Most recently at the Global Hackathon Finals at Facebook, we won First Place.

Since writing this post, I attended another hackathon, HackCU V, where my team won second place. You can read about it in my HackCU V blog post.

As you can tell, I have some experience with hackathons, and a good track record of success at them as well. However, hackathons are a team effort. Three of the hackathons (Xilinx, MHacks, Facebook) I was on a team with Sam Sartor. Three of the hackathons (MinneHack, HackCU, MHacks) I was on a team with Robby Zampino. Two of the hackathons (MinneHack, HackCU), I was on a team with David Florness. Two of the hackathons (HackCU, Facebook), I was on a team with Jack Garner. Two of the hackathons (Xilinx, MinneHack), I was on a team with Jack Rosenthal. Two of the hackathons (MHacks, Facebook), I was on a team with Fisher Darling. One hackathon (Xilinx), I was on a team with Daichi Jameson. Each of them were amazing teammates at the various hackathons, and I definitely would not be writing this article if it were not for each of them.

To answer the actual question though, why should you listen to me? No real reason, actually. I’m just someone who has some experience and some degree of success and I hope that you can learn from both my mistakes and my successes.

The rest of this article is split into a five sections, each dealing with a separate part of hackathons.

- How to form a team for a hackathon.

- How to prepare for a hackathon.

- What to do at a hackathon.

- Things to do during hackathon demos.

- General tips.

1. How to Form a Team for a Hackathon

If you want to win a hackathon, you need a good team. If you are the type of person who is inclined towards leadership, then you should be actively looking for people who you want to be on your team. For me, since I’m in the Mines ACM chapter, I have formed teams with people within that group.

The most important thing is to make sure that you like all of your teammates. You will have to deal with them for an entire day (sometimes more), so the last thing you want is unnecessary tension within the team. Two other important qualities of hackathon teammates are a passion for engineering (hackathons are mini tests of engineering prowess) and the ability to compete and work hard, while still having a ton of fun.

You may notice that I do not consider “technical competence” to be one of the top three most important qualities in a hackathon teammate. That’s because I believe that people who are diligent and passionate can overcome technical incompetency fairly easily. This is not to say that technical competence is not a factor to consider, however. In fact, I generally try to ensure that I cover my own weaknesses with my teammates. For example, Robby is an Electrical Engineer and has a lot more hardware experience that I do (my knowledge is approximately zero in that department). Sam is great with mathematics and algorithms, and just is generally one of the best programmers that I know.

Since technical competence is not a large factor in my decisions for who to ask to be on my teams for hackathons, I often like asking some underclassmen to be on my team. For HackCU, I asked Jack and David (both freshmen) to be on my team. I knew they were pretty good students, and they were involved in ACM projects so I was pretty sure they’d do well at the hackathon, but they definitely out-performed any of my or Robby’s expectations. They were integral to our success at that hackathon. For MHacks, I asked Fisher (freshman) to be on my team. He likewise was a integral part of the team’s success at both MHacks and the subsequent Facebook hackathon.

2. How to Prepare for a Hackathon

Besides putting together a team, there are a few things which you should probably do before the hackathon even starts. Some teams do a lot of preparation, and even come to the hackathon with an idea. I’m not that organized or proactive, but I do try and prepare myself for the hackathon. Here are a few tips:

Do your homework. Your literal homework. It’s not very fun if you have to worry about doing homework during a hackathon. Make sure that you get ahead on your work so that you don’t have to stress about it or feel like you need to be getting other stuff done the whole time.

If you aren’t in school, make sure that you clear your other responsibilities (whatever they may be) out of the way.

Start thinking about what problems you may want to solve at the hackathon. Keep track of all the times you think to yourself, “hey, it’d be cool if…” and “man, this is terrible”. Just keeping track of this will get your creative juices flowing. It is a lot easier to steer a moving ship than one which is still. The same applies to your brain as it explores the set of problems which you could attempt to solve.

In addition to keeping your eyes open for things that bug you, start thinking about what technology you want to use at the hackathon. This requires that you are in-tune with the current state of the tech industry and know what interests you. Often, I’ve shown up to a hackathon with a hammer (technology) looking for a nail (problem).

Think big. Think of lots of ideas that are super big. Sometimes it’s useful to start with huge problems like “world hunger” and then think about different problems in that space and see if some cool idea arises from that.

One example of this was the Facebook hackathon. I’d been wanting to do indoor mapping using just the fire escape floor-plans of buildings for a while, and the hackathon was a great opportunity to take a stab at it.

Bring all the electronics. Does your computer have ethernet? If not, get an adapter. At good hackathons, they will have wired connections for you. Are you driving to the hackathon? Bring external monitors as well!

Do you have some cool electronics lying around (servos, Raspberry Pi’s, arduinos, Wii-Fit Boards, etc.)? Bring them if you can! If you are driving to the hackathon, then you pile all of your junk into your car. That’s how we won HackCU, we had a Wii-Fit board and some other electronics, and we built our project around those components.

3. What to Do at a Hackathon

Now, for the hackathon itself. It’s a ton of fun being at a hackathon, there are always so many people there who are passionate about technology. Make sure you talk to some of them and make some new friends! Also, hackathons always have a bunch of swag. Make sure to get some!

Besides getting all of the goodies, the most important thing to do is figure out what you are going to do for your project. At a 24 hour hackathon, you need to decide within 15 minutes of when coding begins. As you figure out what you are going to do, stretch the boundaries of your idea. Normally the best idea is the one which you are most excited about the extensions that could potentially be made to it after you have a base product developed or that has broad applications in areas you care about. For example, when we were at Facebook, we thought the concept of indoor navigation using AR was great, and we thought of a ton of extensions to the basic idea including collaborative map-making and multiple story mapping.

Once you have a great, big, grand idea, then it’s time to boil it down to a minimal proof-of-concept. Make sure that you don’t loose track of the bigger picture though! (The big picture helps a lot with demos.) Determining what the minimal proof-of-concept entails is a nontrivial problem. Here are just a couple of tips which might get you going in the correct direction:

Think about the primary user flow. What will the user have to do to accomplish the purpose of your application? For example, at MHacks, the main user flow did not include login, so we didn’t spend any time on it. (In fact, login would have just hindered our demo.)

Think about gimmicks, that is, things which will make your hack memorable. Sometimes this is something physical. For example, at MHacks we had a box with a little Arduino-controlled flag which popped up when an upload finished (like a mailbox).

Think of a tagline for your project. What would you tell a marketer your app does? Make sure your project actually does that (or something approximating that).

Think about how you can split up the work. It’s best if you have \(n\) fairly disjoint pieces of the project, where \(n\) is the number of people on your team. This will allow you to diverge and work separately, maximizing the man-hours available, and minimizing the amount of time which you are blocked by each other.

WarningDon’t go overboard with this, you want to have the pieces of your app working together as soon as possible, so don’t diverge too much that you don’t communicate with one another. We made this mistake at MHacks, and we didn’t connect everything up until the last hour of the hackathon (and that was a 36-hour hackathon, so that was fairly impressive).

I always strive to learn something new at each hackathon. We took this to the extreme at Facebook by learning Kotlin and Android development at the hackathon. That was a risky strategy, but it worked out, and I learned a lot while doing so.

So now you know what you are all working on, it’s time to get coding! You’ve prioritized a set of components to implement, but what about the micro-decisions about how to implement those features? Rule number one at a hackathon is to optimize write-time over run-time. Who cares if your algorithm is \(\mathcal{O}(n!)\)? Most likely, you will have \(n < 5\) anyway, and even factorial algorithms are fast enough. Who cares if you have to cast everything 100 times? If doing something nasty prevents even a quarter-hour of refactoring, then it’s worth it. It’s a hackathon after all.

Rule number two, test early, test often. Try to have something working at all times. That way if everything goes south, you can at least save face and have something to show. In order to do this, you need to ensure that you are communicating constantly. That way, you can integrate and test your components as often as possible, and reallocate development resources if someone get blocked.

And that’s a great segue to the third rule: don’t be blocked. Blocked people don’t write code that gets demoed. Don’t be blocked. If you need help, see if anyone on your team can help. If they can’t immediately, try Googling a bit more, and then if necessary, pair up with someone and figure it out together.

At some point, it may be the case that a significant portion of your team is blocked. In this case, the fourth rule applies: be willing to pivot. Don’t ever be too attached to any part of the application that you are willing to drive yourself into the ground in an attempt to get it to work. In fact, don’t even be too attached to your entire idea! At MinneHack 2018, Sam’s team scrapped their entire project midway through the hackathon yet ended up coming back to win second place!

Even if your idea changes significantly during the hackathon, it is important to keep this next rule in mind: constantly think about what to demo. Make sure that you have an idea of what you want to show to the judges at all times. Any time coding anything that will not be shown to the judges is a waste of time (unless it’s for a contingency plan, such as using GPS instead of ARCore to locate the user).

Now, although you shouldn’t be too attached to your idea that you aren’t willing to jettison it, you should balance that with this next rule which is to sell the idea to yourself. Even if you don’t like the idea that much (maybe you were overruled by your teammates when you were deciding what direction to go, I know the feeling, I’ve had that happen to me, and I’ve done it to others), make yourself like it. No, make yourself love it. If you aren’t convinced it’s amazing, you won’t convince the judges that it’s amazing.

Which leads us to the last rule, and probably the most important one: have fun! Yes, it’s a competition, but this is also what you enjoy doing. You are there to write a bunch of code, eat some junk food, and hang out with friends. Winning is just an added benefit.

4. Things to Do During Hackathon Demos

In the last section, I kept mentioning demos. Why? Because they are important! Even if you have the best project in the world, if you can’t demo it effectively, you don’t win. Here are a few tips to make your demos amazing.

Make sure that you have a good motivation. Don’t make it too contrived. It doesn’t have to be your sick grandma that inspired you, it can just be that you are terrible at navigating new buildings, or that parking is a nightmare at school. Anything to let the judges connect with your project is good.

Do some research to see if there is compelling data to support your claims. A lot of times you can get away with just spewing anecdotes, but often, having hard data to back up your assertions can increase your credibility. We did this at MHacks when we looked up how many people have access to SMS and how many have access to the Internet. We noticed that there’s a 1 billion person difference and we used that as one of our marketing taglines: “bringing data to the next billion people”. We didn’t cite the organizations whose statistics we used in our demo, but we had them if we were further probed.

Demos should follow a story arc like the classic “hero’s journey”. Who is the hero? Your app! Make sure to quickly present the problem, then pow your app solves all your problems. Then show them how it does so. This how part of the demo should take up the majority of the time. At the end, try and save time for a couple of sentences about the future of your app.

Make sure you have your demo somewhat scripted (who will say what, etc.), but don’t script it too much that it feels fake. Be natural, be excited, be human.

Since you probably don’t have every single word scripted, make sure that you at least have a list of all the words and phrases that you really want to make sure you say. You may not hit all of them, and that’s ok, but try and say as many of them as you can. For example, at HackCU, we made sure to always describe our app as “distributed inventory tracking” that uses “IoT” and “cloud computing”. At Facebook, we made sure to always mention that it used “AR”, “structure from motion”, and “simultaneous location and mapping”.

Be sure to show the features of your app, not the technology or code behind it. In the real world, features (not code) are what make companies money. At a hackathon, features (not code) are what make you win.

Of course, it’s smart to talk a little bit about the technology you used (especially if you are targeting a technical sponsor prize, or you are using a cutting-edge technology), but that should not be the primary focus of your demo.

This balancing act is important, especially with non-technical judges. When you start “talking computer” at them, their brain turns off and you are automatically out of the running. However, if you just mention a couple of buzzwords associated with your project, they may think “hey, that’s something my engineers talk about a lot, these people must be smart!”. With a technical judge, they hear the technology that you are using and their appetites are whetted enough that they may have questions about it, and that’s where you can let the technical aspects of your project really shine. Always be ready to explain in more detail how you used each of the technologies you mention.

After your demo (and maybe during it), the judges may have questions about what your app can do. Always say that your app can do whatever they ask if it can do. If the judge asks if it can make breakfast, think of some way that it can help them make breakfast (even if that’s an entirely ridiculous idea).

5. General Tips

Everything I’ve mentioned above is important, but there are a couple of things which just don’t fit into any of the categories because they are much more general. Here are my general suggestions:

Back each other up, especially during demos. If somebody is totally bombing the demo, do something to rescue the situation. The classic “as you can tell, it’s very complicated… so now we want to {do something else that is not whatever train wreck you were on before}” is a good go-to.

However, this applies to more than just demos. This also applies to coding and general wellbeing. Having unhappy teammates is not good for many reasons: they don’t write good code, and they are your friends, so you should care about them!

Pretend to know what you are doing. Fake it ’til you make it is a real strategy at hackathons. I’ve faked being an FPGA expert, a voice-over artist, a blockchain developer, an IoT wizard, an AWS specialist, a frontend developer, an Android developer… the list goes on.

Respect the other competitors. They are taking their time to be there, so say hi to them, if they are willing to share what they are working on, be genuinely interested. Who knows? Maybe one of them will be your future co-worker!

Everything that you ever learned about teamwork and being a decent human being applies.

Lastly, have fun! Be competitive, but not too competitive. Don’t let your competitiveness take away from the fun of hanging out with friends for 24+ hours while coding and not sleeping.

There you have it! Those are my tips on how to win a hackathon. Hopefully they’ve been helpful for you. Do you think I’ve missed something? Do you have any additional tips? Comment your thoughts below!

Happy hacking!

Many people have a misconception of the word hack. In the common vernacular, hacking is used to refer to an act which is more correctly described as cracking. Crackers are people who try and break in to systems (either maliciously or as white-hats). Hack on the other hand is an word describing the quality of a technical idea/project. Hacks are things which work, but are very messy. Think of it like using duct-tape to hang something up on a wall instead of doing the “right” thing which would be to hang it up using a nail. ↩︎